From science genius to head of state, the many lives of Armen Sarkissian

By Araks Kasyan, Photography by Davit Hakobyan

Armen Sarkissian’s life could easily be mistaken for the story of several remarkable people fused into one. Born in 1953, in Yerevan, he has traversed worlds that few can imagine: the abstract elegance of theoretical physics, the high-stakes realm of international diplomacy, the calculated risks of entrepreneurship, and the quiet, reflective space of a statesman. In every chapter, one thread remains constant: an insatiable curiosity and a profound sense of duty.

“I think I had several lives, and each time the change from one life to another was a sort of act of God,” he reflects. “I was not planning for it to happen, it just happened because the world I lived in was becoming more and more unstable and unpredictable. The first big bang was the collapse of the Soviet Union.”

Growing up in the USSR, his natural talent for science became apparent early. “I was sort of years ahead from my friends, especially in natural sciences—physics, mathematics. Being a young person, you could ask questions in science, even question Albert Einstein, but you couldn’t do that in history classes. That shaped a habit in me—I don’t like environments where communication is based on politically correct rules. You have to question what doesn’t feel right.”

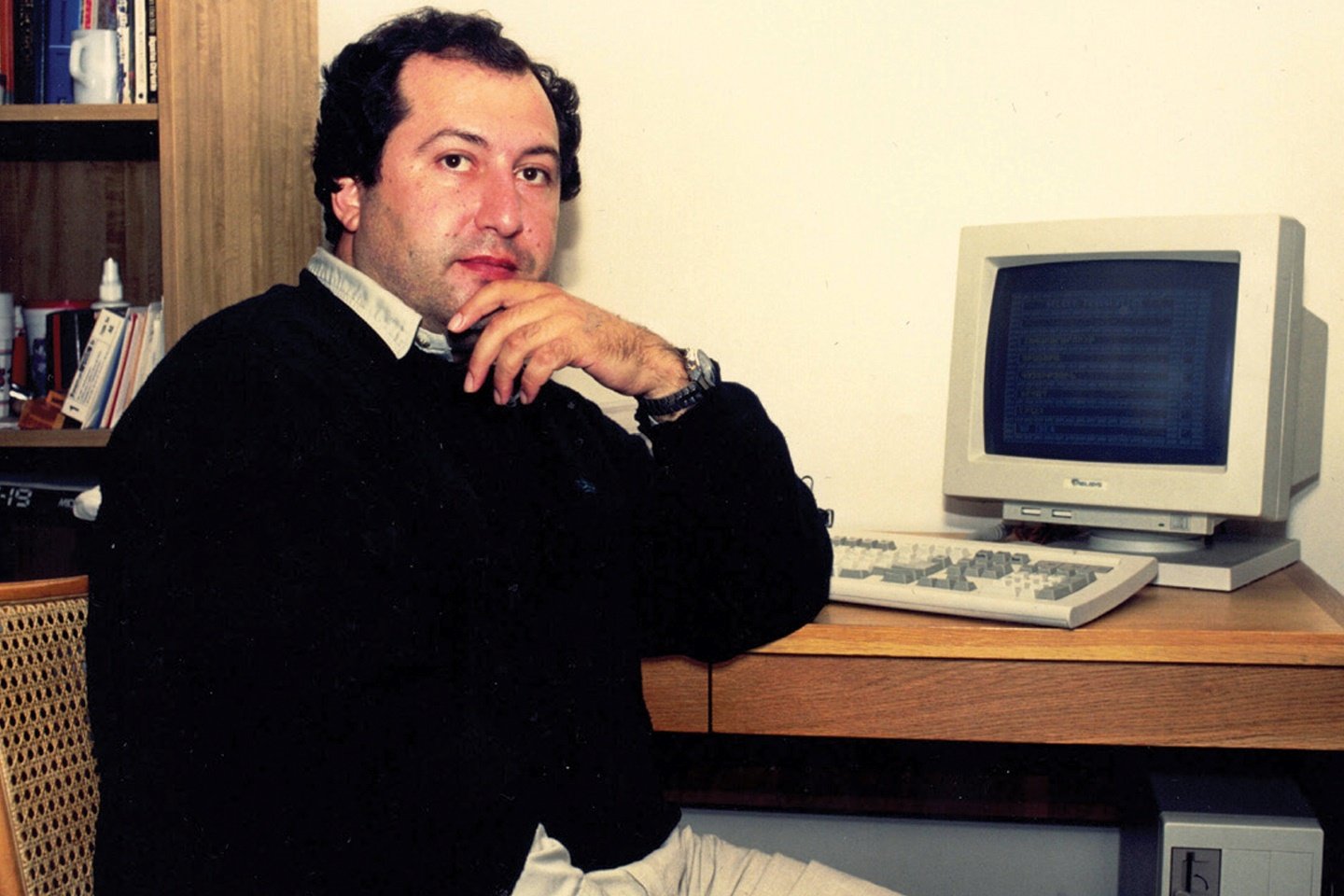

Sarkissian at his desk in Yerevan, Soviet Armenia, with the IBM PC XT machine on which he perfected Wordtris, 1980s.

This questioning mindset propelled him into the physics department of Yerevan State University, where he distinguished himself early, earning prestigious Lenin stipends and embarking on research in the theory of relativity and gravitation. His work drew attention both in the Soviet Union and abroad. Yet his early successes were not without tension. “One negative experience was being questioned by KGB officers about letters from Professor Nathan Rosen in Israel—a very famous scientist who worked with Albert Einstein. They thought these were spy letters, but they were just physics papers. On the positive side, my work caught the attention of Professor Lagunov, Rector of Moscow State University, who invited me to Moscow. That was crucial in my life.”

We were all young and believed in the fantastic opportunity for our nation to become strong, powerful and successful. At first, I thought I could do science and diplomacy together, but I realized this was impossible. I had responsibilities to my country, and I chose service.

Then came Cambridge University. In 1984, after six refusals by the Soviet government to travel abroad, Sarkissian received an invitation from Sir Martin Rees, later Astronomer Royal and president of the Royal Society. With personal guarantees from his mentors, he was finally allowed to go. “Landing at Cambridge as a visiting researcher created a huge scientific network for me. My family, however, was kept as hostages back home.” Among his friends at Cambridge, where he held discussions and debates with Nobel laureates, were the late Stephen Hawking and Venkatraman “Venki” Ramakrishnan, a structural biologist who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2009.

Amid his academic success, Sarkissian found time for invention. “With some colleagues, we created a game called Wordtris. It became part of Tetris Gold, the number one game for five or six years. I had a life in science that I loved, but the world was shifting around me.”

The late 1980s brought seismic changes in Armenia: the independence movement, the Karabakh conflict, and the devastating earthquake. Though abroad, Sarkissian found himself drawn to serve his nation. “I was helping journalists and researchers travel to Armenia, answering questions, assisting wherever I could. When Armenia became independent, I was in Yerevan and later met with President Levon Ter-Petrosyan whom I knew from Matenadaran. We had a deep discussion. And then this is where another Act of God happened—Ter-Petrosyan asked me to help open the embassy in London. I was reluctant—I am a scientist, not a diplomat—but Armenia had just had this rebirth and I felt it would be an abdication of duty to decline this invitation to serve the Motherland.

I was a zero diplomat with zero experience in politics, but I returned to London with a paper signed by Ter-Petrosyan. The Eastern Department at the Foreign Office was shocked because I was the first from the former Soviet Union countries to come and claim that I wanted to open an embassy. But they were very helpful. So I started learning by meeting people. The Armenian community in London was extraordinarily supportive—they gave us Armenia House near St. Sarkis Church for one pound a year and covered all the expenses. They raised money to support the embassy because the Armenian government didn’t have money at all.”

During every visit to Gyumri, President Sarkissian greets his friends at Aregak Inclusive Bakery-Café with the same heartfelt hug.

President Sarkissian with His Holiness Pope Francis at the Vatican, October 2021.

Sarkissian helped establish Armenia’s diplomatic presence across Europe. He became Armenia’s first ambassador to the Vatican, the European Union, NATO, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Belgium, and served as “Senior Ambassador” to Europe.

“We were all young and believed in the fantastic opportunity for our nation to become strong, powerful and successful. At first, I thought I could do science and diplomacy together, but I realized this was impossible. I had responsibilities to my country, and I chose service.”

For Sarkissian, this decision was rooted in a sense of duty inherited from his parents, who returned to Armenia from the diaspora in 1946 despite many opportunities abroad. “My parents could have gone to live in Europe or America after the war but they decided to come to Armenia,” he explains. Sarkissian recalls his late mother’s words in her final days: “When I die I will not have anything that you can inherit from me… The only thing that I can give to you is Armenia.”

While he continued to engage with science occasionally, giving lectures and attending conferences, his primary focus shifted to diplomacy. The early years were a learning curve, but he worked with experienced colleagues and quickly adapted, building Armenia’s presence abroad from a scratch.

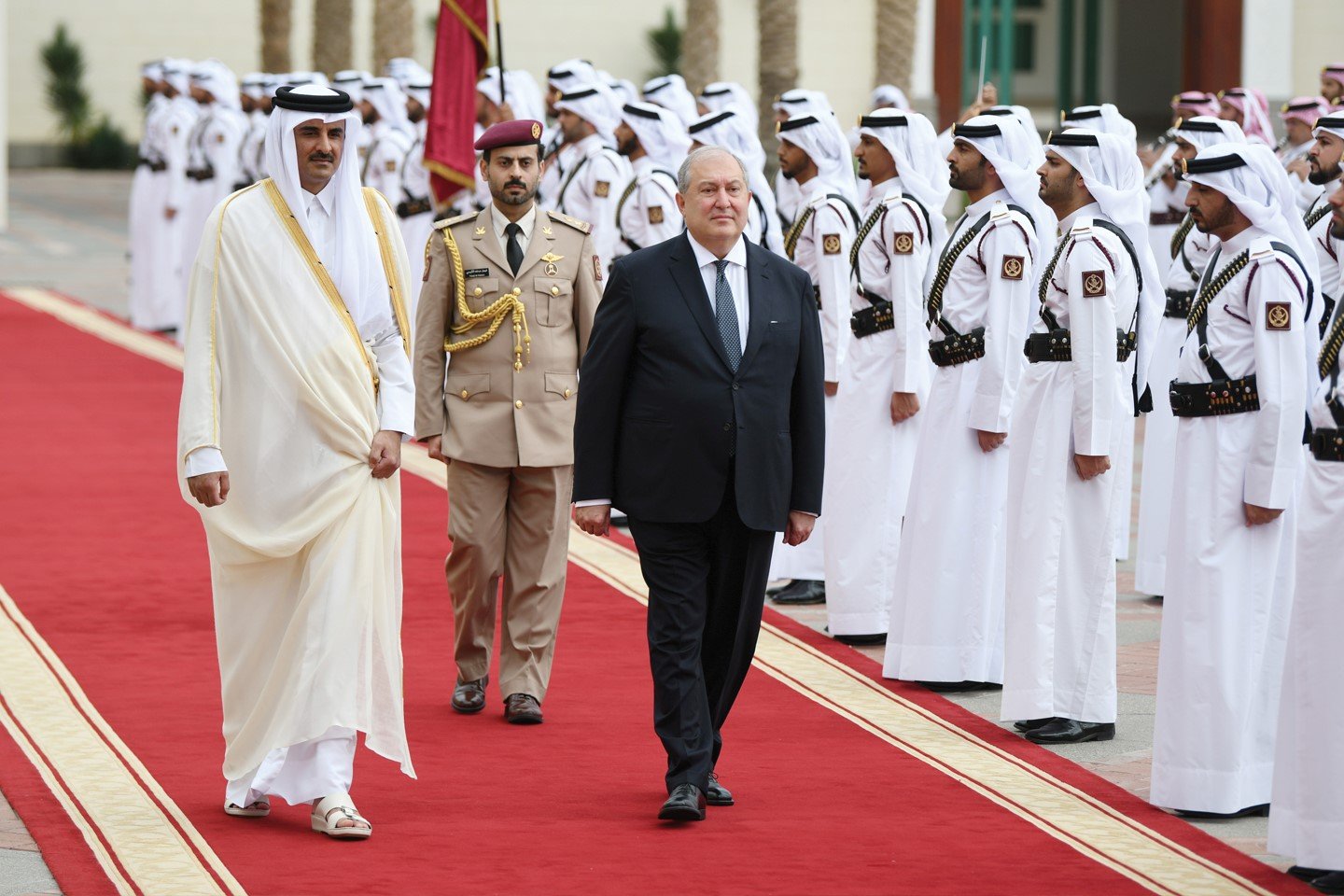

Official welcoming ceremony for President Armen Sarkissian at the Diwan, the residence of His Highness Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, Emir of the State of Qatar, November 19, 2019.

Armen Sarkissian’s life in public service has been guided by a principle that is both simple and profound: duty. “I felt that I had a duty. That duty became stronger,” he reflects. For Sarkissian, serving his country was never a career choice—it was an obligation, a moral compass that shaped every decision he made in public service. “You have to believe in what you are doing. Never lie to yourself,” he emphasizes, describing a personal philosophy that kept him grounded amid political turbulence.

For Sarkissian, leadership is inseparable from humility and a willingness to learn. He recalls an early seminar at Cambridge University with Nobel laureate Hannes Alfvén, the father of plasma physics. As a young researcher, he boldly questioned Alfvén’s conclusions—a move that could have been risky in the Soviet scientific hierarchy. Yet, to his surprise, Alfvén invited him to lunch afterward, telling him, “Yes, I’ve done great work, but the young generation may end up achieving far more.” It was a lesson for a young scientist: no matter how high one rises, listening, learning, and respecting others is essential. “Being whatever you are—prime minister, president, ambassador—you have to learn every day, listen to advice, and consider other opinions to find the truth and the right solutions,” Sarkissian says.

Talking about civil service, he emphasizes that it’s more than a job—it’s a responsibility to the nation. He argues that everyone in public service, from clerks to ministers, should approach their work with the dedication of a soldier, fully committed to the success of their department or a country. “Civil service must be non-political,” he stresses. Loyalty, he says, is to the country, not to any party or ideology.

In Berlin’s Federal Chancellery, President Armen Sarkissian and Chancellor Angela Merkel discuss strengthening Armenian-German relations, November 28, 2018.

Looking back at his decisions, Sarkissian does not dwell on regrets. “It’s not useful to go back and say, ‘If I had done this…’ It’s healthier to analyze what you did right, what you did wrong, and learn from it. Every decision that I made I tried to be honest with myself and my principles.”

He recalls moments when circumstances tested him profoundly. “I became prime minister in 1996 because I felt I could help the country with my experience. But then again it was an Act of God—after several months I was diagnosed with cancer and had to resign.”

After recovering from illness, he left the public service, he devoted himself to business, academia, and international consulting. His Eurasia Center at Cambridge University educated hundreds of young people, including a great many Armenians. “I was successful in many sectors—energy, telecom, food—but eventually realized I was not fully happy.”

When he was invited back to diplomatic service in 2013, he accepted the role of Armenia’s ambassador to the UK, a position he held until 2018. True to his principles, he chose not to receive a salary and to cover his own living expenses, insisting that public resources should not be spent on him, and paid out of his pocket to renovate the embassy.

When Armenia shifted to a parliamentary system, Sarkissian was invited to serve as president. He accepted with the expectation of wider responsibilities in foreign affairs, investment, education, and science. “Eventually I made the decision to come back,” he recalls, “but with the belief that constitutional changes were needed to truly balance power.” Determined to serve with integrity, he donated his salary to charity and continued living in his own home, avoiding any burden on the state.

Sarkissian has been credited with ensuring that the Velvet Revolution remained peaceful. As the Spectator, the world’s oldest magazine that used to be edited by former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, wrote: “The Velvet Revolution was not preordained to be peaceful. It was Sarkissian’s intervention that kept the peace.” The same profile quoted a foreign ambassador, who noted that “Sarkissian is in a different league” from other politicians in the region. He’s a scientist. He’s a capitalist, but he didn’t have his fingers in the pie here. He made his fortune by working hard in the West. He cultivated really strong relationships as a diplomat and could get a meeting with almost any world leader. For a tiny country, that is a huge asset.” The same diplomat bemoaned the fact that “Sarkissian was just not utilized during the war… Sarkissian’s office had no real authority. If he had had a say in how the war was run and how the peace was negotiated, I can confidently say that country would not be suffering so much today.”

Sarkissian oversaw an annual conference that turned Dilijan into the Davos of the Caucasus once a year, drawing international business leaders, diplomats, politicians, authors, scientists, and public intellectuals to Armenia. In 2021, Sarkissian travelled to Saudi Arabia, where he was received by the Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the de facto ruler. This was all the more remarkable because Armenia had no diplomatic relations with Riyadh at that point. As the Spectator observed at the time, “It was another example of Sarkissian using his extensive personal friendships cultivated as a private businessman to the benefit of his beleaguered country.”

The new world is a world of technology, of rapid decisions, of networking and being successful. In this environment, honesty remains just as essential, but new qualities are required as well.

Stepping down from the presidency, Sarkissian admits, was harder than stepping in. “Saying, ‘No, I will not serve further,’ was a hundred times more difficult than continuing,” he reflects. The turning point came when he asked himself whether he was truly effective. “Was I becoming someone just sitting there, enjoying being president? Did I have a real impact?” His answer was no. Feeling that his experience and advice were not fully heard, he decided that remaining in office would only mean pretending. In the end, stepping aside felt like the only way to remain true to his principles.

Reflecting on the future, Sarkissian believes the next generation of leaders will face a very different world. “The new world is a world of technology, of rapid decisions, of networking and being successful. In this environment, honesty remains just as essential, but new qualities are required as well.” Leaders, he says, must be smart, understand technology, and know how to use it.

Small states, in particular, demand dynamic leadership. To illustrate, he turns to a metaphor: “If you are a sea or an ocean, you don’t need activity, because there are currents, winds, water is always moving. But if you are a lake, and you don’t bring in new water, take some water out, have rain coming, a dynamic process—that lake after a while will become a swamp. So if you are small, you have to be very dynamic.”

For Sarkissian, real leadership also demands knowledge, and a sense of mission, and what he calls “smart force”—leading by example rather than pressure. Public life, he warns, is rarely rewarding and often feels like sacrifice, which is why only those with a true calling should enter it. “You have to have a mission,” he says. “Otherwise, you are wasting your time.”

Asked what keeps him inspired after decades in public service, Sarkissian doesn’t hesitate: it’s curiosity. “I am living a life where I am starting to learn something new every day,” he says. Since stepping away from Armenian politics in 2022, he has focused on projects that connect his global vision with his lifelong love of science and innovation. “I made a decision not to be involved in political life. But if there’s a crucial moment to help Armenia, I am there anytime. If you need me, ask me, I will be here to help.”

Sarkissian has turned his attention to small states, writing The Small States Club: How Small Smart States Can Save the World, a book that proved a critical and commercial success, drawing applause from such luminaries as Henry Kissinger, Shashi Tharoor, and Kishore Mahbubani. The Small States Club, while telling the stories of ten countries, highlights their surprising global influence. “If you take the innovation index, the first ten states are small states. If you take the e-government index, again, the top ten are small states,” he notes. For him, this is proof that success in the modern world is measured differently than in the past, and that agility often trumps size. A revised and updated paperback edition of the book is on the way, and Sarkissian, ever restless, is at work on an initiative to create an international platform he calls “the S20”—a club of the world’s most innovative and successful small states.

Equally close to Sarkissian’s heart is the future of health and longevity. “Health is the most important thing in human life,” he insists. Believing that breakthroughs in AI and quantum computing will transform medicine, he founded the ATOM (Advanced Tomorrow) Institute, based in the United States, to focus on well-being and longevity. The institute has already hosted two successful international conferences, and he sees enormous potential in this frontier.

Though busy with global projects, Sarkissian admits that the hardest part is staying silent about Armenian politics. “That’s the one rule when you think of civil service and serving your country. There are times when it’s better not to talk. I had my time as president and prime minister, I did what I could. Talking now is not going to help much—unless I am asked to talk.” Still, he continues to share his ideas in regular opeds published in the world’s leading newspapers and periodicals, including the Wall Street Journal, the Daily Telegraph, and Time. A highly sought after speaker, he also finds time to address audiences at international conferences and universities, where he has a reputation for setting aside notions of political correctness in favour of frank discussion. It is said that a number of prominent leaders in politics, policy, and business also lean on Sarkissian for advice. Yet, above all, Sarkissian’s devotion remains deeply personal: “I can speak about many small states with my mind, but my heart belongs to only one—Armenia.”

AGBU – The biggest global Armenian organisation with headquarters in New York

Recent AGBU magazine (Pages 22-27):

https://online.fliphtml5.com/fqpe/enhh/#p=1

Date

7 December 2025